HOT NEWS !

Stay informed on the old and most recent significant or spectacular

nautical news and shipwreck discoveries

-

Seeking booty, archaeologists dive to Blackbeard's pirate ship

- On 05/10/2010

- In Underwater Archeology

North Carolina Office of Archives and History

North Carolina Office of Archives and History

From Fox News

Archaeologists seeking ancient pirate booty are heading back to sea off North Carolina's coast -- a continuing effort to recover artifacts from the wreck believed to be Blackbeard's flagship.

The boat, called Queen Anne's Revenge, is believed to have sank in 1718 near Beaufort, N.C. Archaeologists in the state aim to save a dozen cannons -- up to 8 feet long and as much as a ton in weight -- and the ship's 1,800-pound anchors by preventing the process that corrodes iron in saltwater.To do so, they apply skinny aluminum rods to the boat that act as annodes, supplying an electrical charge that inhibits corrosion.

"Visibility on the bottom is about six inches with a dive light and zero without," wrote a team member on the restoration effort's Facebook page Monday afternoon. "Occasional surge shifts you back and forth a few feet. Working on repositioning the 6" suction and preparing to re-expose the grids covered over by last week's weather."

The Daily News of Jacksonville reported that last week's heavy rain and winds kept the team from investigating the wreck.Instead, the chief archaeologist and diving supervisor for the project said he and his colleagues worked on land.

QAR archaeological field director Chris Southerly said the team knew it would lose days due to bad weather.Ocean swells can delay diving, and Hurricanes Igor and Julia already roiled the seas.

Water temperatures earlier in October trend towards 79 degrees -- more appealing than the 10-degree-cooler temperatures of late October.

-

'Lost on the Lady Elgin': A new account emerges

- On 05/10/2010

- In Parks & Protected Sites

By John Gurda - Jsonline

Lake Michigan is acting up again. More than once in the past few weeks, high winds have whipped the water to a froth even inside the harbor, and any boat venturing out onto the open lake was in for a wild ride. We have entered what early Milwaukeeans dreaded as shipwreck season.Ever since regular navigation on the Great Lakes began in the 1820s, thousands of vessels have gone down in "the gales of November"- and the gales of September and October as well.

This autumn marks the 150th anniversary of the worst shipwreck on the open waters of the Great Lakes. The doomed vessel was the Lady Elgin, a side-wheel steamship that has achieved legendary status in our region's marine lore.Not only was the loss of life on the Lady Elgin appalling, but most of the victims were Milwaukeeans, and their fate was tied directly to tensions that were tearing the country apart in the years before the Civil War.

The story of the sinking is told in a new book, "Lost on the Lady Elgin," by Valerie van Heest, an author, designer and, importantly, a diver who has explored the vessel's wreck more than once. Van Heest's account is both the most complete and the most authoritative ever written on the tragedy.

The last voyage of the Lady Elgin was, in essence, a fund-raiser gone terribly awry. Most of its passengers were affiliated with the Union Guards, an Irish militia company based in Milwaukee's Third Ward.The unit's commander was Garrett Barry, a West Point graduate who was also active in Democratic politics; local voters made Barry their county treasurer in 1859.

Wisconsin was a hotbed of anti-slavery sentiment at the time, particularly under Gov. Alexander Randall, a "fire-breathing" abolitionist.The Wisconsin Supreme Court went so far as to declare the Fugitive Slave Act, a federal law safeguarding the rights of slave owners, unconstitutional. No other state took a stand so courageous - or so potentially seditious.

Bracing for a possible confrontation with federal authorities, Randall called for a declaration of loyalty from the state's militia companies. Barry, a Democrat, told Randall, a Republican, that taking sides against the United States "would render himself and his men guilty of treason." Randall promptly stripped Barry of his commission and disarmed the Union Guards.

Militia companies of the era were largely volunteer groups, typically organized along ethnic or class lines, whose activities were as much social as military. Randall could take their rifles away, but the Union Guards owned their own uniforms and their own band instruments.No one could keep them from meeting and marching - or even from owning guns. In June 1860, with help from a sympathetic congressman, Barry purchased 80 government-surplus muskets for $2 each.

The $160 bill would top $4,000 in current dollars. Instead of assessing themselves for the muskets, the Union Guards decided to raise the money by sponsoring an excursion to Chicago - aboard the Lady Elgin.

Launched at Buffalo in 1851, the Elgin was a lavishly appointed "palace steamer," with 66 staterooms on its upper deck, a smoking lounge for "gentlemen" and a grand staircase to the lower deck.Although it could accommodate hundreds of passengers, the ship doubled as a freight-carrier, offering regular service between Chicago (its home port), Milwaukee and destinations on Lake Superior. It also attracted a regular stream of excursionists.

Read more... -

Lake Erie shipwrecks

- On 05/10/2010

- In Parks & Protected Sites

Photo Jack Papes

Photo Jack Papes

By Shannon M. Nass -The Post Gazette

The marine forecast is perfect. Winds are southwest at 5 knots and waves are 1 foot or less. The surface of Lake Erie is almost placid, beckoning a local diver to don his gear and dive 200 feet to the lake floor below.

He begins his descent through tepid water, but as he passes through the thermocline the water temperature drops 30 degrees, cold water envelops his body and visibility is limited.

Suddenly, out of the darkness the mast of a ship comes into view, beckoning from its watery grave. The diver's doubt is replaced by exhilaration as the wreckage of a ship from the 1800s is unveiled, perfectly preserved in all her glory.

For centuries, Lake Erie has been a bustling thoroughfare. But weather-related sinkings, collisions and other calamities claimed many vessels, leaving the lake floor littered with their remains.It is estimated that the Great Lakes are home to 8,000 shipwrecks, with approximately 2,000 located in Lake Erie. Most of the wrecks have yet to be discovered, drawing divers from all over the world in hopes of being the first to uncover a lost piece of history.

"I can imagine standing at the pier on Lake Erie over 150 years ago. It must have been just a massive traffic jam of ships on the horizon," said Jack Papes, a diver from Akron, Ohio.

Papes has been documenting and photographing the wrecks of the Great Lakes for the past 10 years and has visited nearly 120 of them. He's traveled all over the world to dive to shipwrecks, but he prefers the ones close to home.

"People have asked me, if you could have an all-expense paid trip to anywhere on the planet, where would you go," said Papes."I tell them, well, I'd be up on the west coast of Lake Huron diving. I think that's some of the best shipwreck diving there is."

-

Underwater archaeology chronicles moments in time

- On 05/10/2010

- In Miscellaneous

Photo Jack Papes

By Shannon M. Nass - Post-Gazette

Before dives on known wrecks, divers research the vessels. Located on the grounds of the Great Lakes Historical Society in Vermilion, Ohio, is the Peachman Lake Erie Shipwreck Research Center, a research facility that documents Lake Erie shipwrecks and offers maritime archaeology workshops.It also serves as the headquarters for the MAST program (Maritime Archaeological Survey Team Inc.), which trains divers to survey shipwrecks.

"Most of what we do with MAST are straightforward, two-dimensional site plans," said Carrie Sowden, archaeological director at the research center."We're looking at how the ship sits on the bottom and mapping all of it out so we know exactly what it looks like sitting on the bottom of the lake."

MAST consists of 200 volunteers devoted to documenting and preserving Lake Erie shipwrecks. They focus on older sites that are more prone to degradation due to frequent visits by divers.

"Nobody's malicious or anything, but once you start having human intervention on a site, it will start to degrade over time," said Sowden. "You know, the little touch here, the sitting down there. We're trying to create a baseline so that we know what is there." -

ECU students explore, document shipwrecks

- On 05/10/2010

- In Marine Sciences

By Ginger Livingston - The Daily Reflector

Efforts to document two shipwrecks in South Carolina's Cooper River by East Carolina University students and researchers ended up with more questions than answers about who used the boats.

Shards of Native American pottery discovered in wreckage at a site called the Pimlico shipwreck have researchers asking if it's evidence that the ship's owners possessed Native Americans slaves, if there was trade between Native Americans and individuals who worked on the ship or if perhaps it's debris that washed in the wreckage.

Discovering such a mystery is what drives students and researchers in ECU's Maritime Studies program.

Founded in 1981, the Maritime Studies program, part of the university's Department of History, offers a master's degree in maritime history and nautical archaeology. ECU's program was the second in the nation and today is only one of four programs in the nation.

“We have an emphasis on field work,” said Lynn Harris, assistant professor of Maritime Studies. Harris came to ECU from South Africa and was an early student of the program.

Teaching students the practical skills needed to work underwater sites routinely places students in the murky rivers and sounds of the Carolinas, the turbulent waters of the Atlantic and even Sweden and Namibia to study shipwrecks.

Students must participate in two field projects before earning their degree.

This requirement sent 20 students and professors to Charleston, S.C., for three weeks last month to study two plantation boats on display at the Charleston Museum and Middleton Place, a historic plantation. They also worked on the Pimlico and another shipwreck at Strawberry Landing, also along the Cooper River.

Because of tidal influences, dives on the two wrecks had to be split with time spent on land recording information about the plantation boats, which were called the Bessie and the Accommodate.

Both were built in 1855 and designed to transport people, crops and other materials around South Carolina's interior waterways.

The Bessie and Accommodate fascinated second-year student Nathaniel Howe, who previously worked on a project restoring a Swedish warship. The exterior hulls resembled Native American dugouts because each was shaped from a single log. However, the two boats' builders shaped the exterior to resemble the hull of a European boat and lined the interior with planks. It was designed to be rowed or sailed, Howe said. While recording its dimensions, the students saw how one boat's user relocated the mast.

“It's amazing how much history is in this structure,” he said.

The students used a piece of equipment called a total station to record a three-dimensional image of a point on the boat. The points are combined eventually to make a three-dimensional model of the boat.

-

18th century ship found at World Trade Center has a name...and worms

- On 02/10/2010

- In Parks & Protected Sites

By Stephen Nessen - WNYC News

Few things preserve like dense Hudson River mud. That was proven this summer when workers at the World Trade Center site uncovered the skeletal hull of an 18th century ship at the site of a future car park. Twenty-five feet below the surface, buried in grey muck in a section of Lower Manhattan that hasn’t seen light for almost two centuries, was the hull of a 32-foot merchant vessel.

On Thursday night, 40-stories above the work site, at 7 World Trade Center, the archaeologists, preservationists and a maritime historian, who teamed up to excavate the fragile pieces, explained what they’ve learned so far, and what it takes to delicately extricate some of the most fragile materials on earth.

Michael Pappalardo, the senior archaeologist with AKRF, the firm hired by the Port Authority to help document the findings, said that the boat, with its shallow hull, was most likely a merchant vessel. Little holes bored into one of the wooden posts indicate the ship spent significant time in Caribbean salt water.The holes were made by teredo worms, also known as the “termites of the sea.” The only reason they didn’t completely destroy the ship is due to the dense, oxygen-less Hudson mud, which kills all bugs.

The origin of the ship remains a mystery, but there are some clues. Pappalardo said that the irregular length of the planks, which are fit together like a puzzle, indicates the ship was built in a small, rural shipyard.

The excavators also uncovered 1,000 disparate artifacts at the site. Pappalardo rattled off a list of antique store items they found: a spoon; dozens of leather shoes; nuts; seeds; a British revolutionary war era button; various ceramic items; various animal bones; including a horse jaw (“I hate to think that was part of food, but I really don’t know,” Pappalardo says); a single coin wedged between two pieces of wood (a common superstitious symbol sailors carried); and a human hair with a preserved louse on it.During one sweltering week this July, the team of two conservators, two marine historians, three archeologists, one photographer and a few construction workers worked to unearth the ship, which they dubbed the “SS Adrian,” after the superintendant of the construction crew.

One of the archeologists, Elizabeth Meade, calls it one of the greatest projects she’s ever worked on, but says it was an exhausting week, and not terribly pleasant, tromping around in the 25-foot hole.“It has a low tide smell, it’s that river bottom, dead seaweed, old oysters kind of grossness that doesn’t leave you for awhile. It earned me the nickname Swamp Thing among my friends,” Meade says.

-

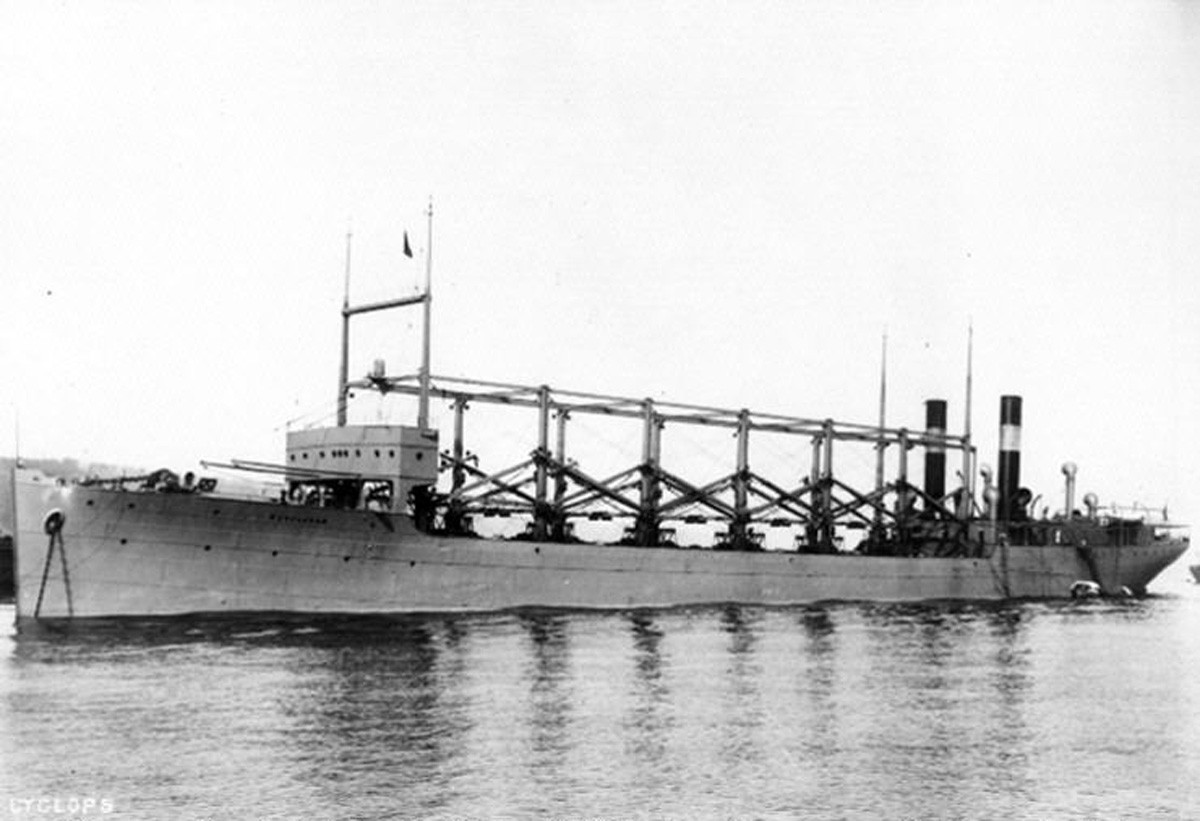

Disappearance of USS Cyclops: Still a mystery

- On 02/10/2010

- In Miscellaneous

By Frederick N. Rasmussen - The Baltimore Sun

The last anyone heard of the Cyclops as it steamed in a voyage that began in Bahia, Brazil, on Feb. 22, 1918, en route to Baltimore with 10,000 tons of manganese ore in its bunkers, was in a telegram to the West Indian Steamship Co. in New York City.

"Advise charterers USS CYCLOPS arrived Barbadoes Three March for bunkers. Expect to arrive Baltimore Thirteen March. Opnav."The next day, the collier departed Barbados on what should have been a routine voyage to Baltimore, even though its starboard engine was damaged and put out of commission during the passage from Bahia to Rio de Janeiro, forcing it to steam at no more than 10 knots.

Brockholst Livingston, who was the 13-year-old son of U.S. Consul C. Ludlow Livingston, recalled in 1929 that the ship's captain, Lt. Cmdr. George W. Worley, and several other guests, including U.S. Consul-General A. Moreau Gottschalk to Brazil, who was a passenger on the ship, had tea at the consulate.

Before leaving, young Livingston wrote that the guests had signed his sister's autograph book and that their signatures were "probably the latest ones in existence."

"No one, of course, thought there was any danger in the voyage. About five o'clock our guests left and we watched them from the beach as they went on board," he wrote.

"There were some blasts on the whistle and the Cyclops backed. Then, going ahead, she steamed south. We did not consider this course odd until a few weeks later when we got a cable requesting full details of her visit to Barbados," he wrote.

It was the last time that any human had laid eyes on the Cyclops as it steamed away into the gathering evening and a permanent place on the roster of vessels that failed to make port.

Every so often during the intervening decades, the fate of the Cyclops makes the rounds.

Maritime historians pored over old documents in dusty archives and libraries, and old salts gathered in waterfront taverns spinning endless theories of what happened to the vessel that was traversing a lonely stretch of the South Atlantic when it vanished without a trace.

The Cyclops, with 309 on board — officers and crew, including 13 Baltimoreans, and passengers — apparently went to the bottom on March 4, 1918.

Among those who lost their lives were three Navy and two Marine prisoners who were being transported to the brig at Portsmouth, N.H.

There were no survivors or wreckage. A couple of boards found by an island hermit, who claimed they came from the ill-fated vessel's lifeboats, were discounted as not being from the wreck, as were bottles with notes, purportedly from survivors, that turned out to be nothing more than hoaxes.

-

Shipwreck reveals treasure box of intact ancient medicines

- On 02/10/2010

- In Underwater Archeology

By Susan Perry - Minn Post

The wreckage of a Greek ship that sank off the coast of Tuscany, Italy, in 130 B.C. has provided modern scientists with the first physical evidence of medicines prescribed by such ancient Greek physicians as Galen and Dioscorides.

And the results are fascinating (well, for medical history buffs like me).

As reported in New Scientist, the millennia-old treasure-box of pills was actually discovered — almost completely dry, remarkably — along with the rest of the shipwreck in 1989, but archaeobotanists only recently got their hands on it.Using DNA technology to analyze the medicine’s contents, the scientists found that each tablet contained more than 10 different plant extracts, including carrot, radish, celery, wild onion, oak, cabbage, alfalfa, and yarrow.

Such plants were commonly used at the time to treat physical — and mental — complaints. Yarrow, for example, was used to staunch blood flow from wounds, and carrot had many uses, including aiding conception and protecting people from reptiles (!), explains New Scientist reporter Shanta Barley.

One of the biggest surprises from the analysis was that the pills contained sunflower. Botanists have long believed that the sunflower first arrived in Europe in the 1400s, brought back from the newly discovered Americas.