VOC Geldermalsen

Porcelain and gold bullion from Asia

By VOC Shipwrecks - Nick Habermehl

It will be more than a year before the Geldermalsen leaves for the Indies on her maiden voyage, but on 16 August 1748, captain Willem Mareeuw van den Hoek can cast off. The crew will have to load and unload many times. First in Batavia, where the Geldermalsen puts into port on 31 March 1749. After that she leaves for Japan on 21 June, where she arrives on 2 August. Once again new cargo is taken on board. On 31 October the ship embarks on the voyage back to Batavia, where she arrives on 10 January 1750.

Via Cheribon (March 1750) and Bantam (April) the Geldermalsen is now directed to Canton to take in goods for Surat. That, again, is quite a voyage and in China it takes months to collect the proper merchandise. Finally, the Geldermalsen leaves for Gujarat where she arrives on 8 March 1751, after having successfully warded off an attack by pirates off the coast of Goa. Once more loading and unloading, departure on 15 April. Via Cochin and Malacca the ship now sails back to Canton, where on 21 July 1751, the Geldermalsen can join the other ships of the VOC who are waiting there to be loaded.

The Geldermalsen's new destination is the Netherlands. A new crew comes on board; mostly they have come along on the Sjandvastigheid from Batavia. The new captain is Jan Diederik Morel, who finds many failures in the Geldermalsen, in spite of the fact that she is still quite new. He sends for spare parts from the Vrijburg and the Sjandvastigheid, for compasses and maps, while a message is sent to Batavia that the cruiser who will tranship the gold in the Sunda Straits should also take on twenty barrels of drinking water, since many of the water vessels on board the Geldermalsen are found to be mouldy.

Batavia has not sent along any foodstuffs for the return voyage, and as much 'ordinary' food as possible is collected from other ships. All in all, this is sufficient for five months. In that time the ship can reach the Cape and stock up on fresh provisions. The daily menu from now on will consist mainly of rice and beans. For the ship's cabin and the sick-bay there are some extra supplies: rice and wheat, 20 live pigs and 4 oxen, 370 pounds of powdered sugar, 5 pounds of spices, 10 pounds of mustard seed, 153 litres of brandy and 270 litres of white wine.

Prior to departure, the clerks in Canton are compiling inventories. Thus the ship is armed with 24 iron cannons and 2 cannons of bronze, 36 rifles and pistols, 100 hand grenades, 25 broadswords, 27 pikes, 3.000 pounds of gunpowder and anything else needed to maintain and use such an arsenal. For troublesome seamen 18 shackles and 24 manacles are taken along.

On 18 December 1751, three weeks later than the Amstelveen who will reach home safely in July 1752, the Geldermalsen leaves Canton. There are 112 people on board.

It is Monday 3 January 1752. After 16 days' sailing the Geldermalsen is near the 55th minute latitude, just above the equator. At half past three in the afternoon captain Morel emerges from his cabin. There is no reason whatsoever to think of a catastrophe: the weather is fine and there is a calm northerly wind. Morel asks the boatswain and third watch Christoffel van Dijk, who is on duty at the moment, how the situation is with regard to the orientation point Het Ruyge Eiland. The boatswain answers that the island is visible to the north-west of the ship. The captain says that at this point of the route Geldria's (or Gelderse) Droogte has been passed and he gives instructions to set a southerly course.

At six o'clock, just before dark, third watchman Jan Delia and two cadets, Arie van Dijk and Anthony van Grauw, climb up for a lookout. There is no land in sight. One hour later boatswain Urbanus Urbani is at work with the anchors.

It is now dark, but just in front of the ship he suddenly observes breakers. He manages to shout that the helm should be hard over, but it is already too late, for with a loud noise the Geldermalsen crashes onto a reef.

Of the crew members, 32 survived the shipwreck; the other 80 went down with the ship. There is no complete list of crew members of the Geldermalsen, though there is a ship's list of the Sjandvastigheid, part of whose crew transferred onto the Geldermalsen in Canton. On this list those who drowned in the shipwreck have later been noted. There are also data from other records. Although the Amstelveen, due to the sudden halving of the annual supply made a record profit, the VOC naturally suffered a loss from the wreck. The entire cargo, valued at fl. 714.963, was lost, plus the gold at a value of fl. 68.135. The ship's hull is recorded as worth fl. 100.000. A total loss of nearly nine hundred thousand guilders.

The discovery by Michael Hatcher

When a ship has lain in water for 233 years, not much is left of it. Only objects of durable material, such as gold, bronze and of course porcelain can survive such a period. Nevertheless, Hatcher and his men, while digging up these treasures, have swum around in a gigantic teapot. It is worth dwelling on this, and to remind ourselves of the important fact that this VOC ship carried tea as her most important cargo. At present attention is naturally focused on the porcelain and gold, but for the Chamber of Zeeland, which was the Geldermalsen's destination, the tea, 686.997 pounds, meant the prospect of a profit of about four hundred thousand guilders.

Not much has remained of the packing material, the wooden chests and the bales but the tea itself, originally a several meters' thick layer, has thickened and thickened again, thus forming a soft protective layer for the rich cargo underneath. For the time to come Hatcher will probably sicken at the mere thought of tea...

We can distinguish three categories of objects brought to the surface by the divers : objects belonging to the ship's inventory, gold and the collection of porcelain.

Hatcher has further recovered two bronze cannons, the only two on board, according to the inventory. There were also 24 iron cannons, but they have suffered far more from the sea water. One of the cannons bears the VOC monogram of the Amsterdam Chamber and the inscription: Mn---- Noordene Landgrave (?) Amstelodami A 1702. The digit 1656 indicates the weight in pounds.

The other cannon, with the VOC monogram and the R of the Rotterdam Chamber, has a more legible inscription, which says: me fecit quirin de Visser Roterodami 1705. The weight indicated is 1702 pounds. Both cannons have two handles in the shape of a curving leaping dolphin. The dates indicate that they were not especially made for the Geldermalsen. It is even doubtful whether they were on board at all when the ship first sailed for Asia. In Batavia and on the way the armament of a ship was frequently changed ...

... For the history of Asiatic ceramics the many martabans are interesting: storage jars for water, oil, preserved vegetables and other items. They are made of thick, brown-glazed stoneware and were traditionally manufactured in South-Chinese kilns. There are various types in Hatcher's find: the low, bulging model with a wide shoulder and tapering at the bottom, the higher pear-shaped model and a small martaban with a clearly pronounced shoulder and a slightly outward-curving wall which only narrows at the bottom.

The study of martabans has lately become a subject of renewed interest. They have been used throughout South-East Asia for many centuries as storage jars, and sometimes, as handed-down family heirlooms, they were even believed to have magical powers. Dated pieces, such as these of the Geldermalsen are rare and very welcome for further study.

For the history of Asiatic ceramics the many martabans are interesting: storage jars for water, oil, preserved vegetables and other items. They are made of thick, brown-glazed stoneware and were traditionally manufactured in South-Chinese kilns. There are various types in Hatcher's find: the low, bulging model with a wide shoulder and tapering at the bottom, the higher pear-shaped model and a small martavan with a clearly pronounced shoulder and a slightly outward-curving wall which only narrows at the bottom.

The second category of Hatcher's find is, of course, the most spectacular: the gold. As Hatcher himself tells in an interview: this is the dream of every diver, the classical children's story of shipwrecks and hidden treasures. It is already an adventure in itself to see such a fairytale come true.

As a matter of fact, Hatcher was lucky. The period during which the return ships carried gold on part of their route was relatively brief: from 1735 until 1760. And of all these ships 'only' two were shipwrecked: the Enkhuizen in 1741 and the Geldermalsen in 1752. The Amstelveen, for instance, who sailed for the Netherlands three weeks before the Geldermalsen, did not have any gold on board at all.

In all, the Geldermalsen carried 147 pieces of gold. Hatcher has found 125 of them. There are 107 rectangular bars and 18 so-called shoes or boats of a more or less oval shape with upright ends. The shoes measure 5.5 x 3 x 3 cm, the bars 8 x 2.5 x 1.5 cm. Bars and shoes each weigh approximately 370 grams or 10 Chinese thaels.

All the gold is extremely pure, about 20 to 22 carats, and stamped with Chinese quality seals. On the shoes we see one or two round seals with the character 'ji', which means 'luck'. The bars have two square seals bearing the character 'yuan' and a gourd-shaped seal with the signs 'yuan ji bao' , meaning 'gold block' or 'valuable' .63 In letters in which the buying-in of gold is mentioned, we read that most of it was bought through the Hong merchant Tsja Hongqua, who got it from Nanking. In those days this was already an important trading centre. Raw silk and Nanking linen are manufactured there and the Chinese merchants in Canton have intensive contacts with this place.

Of greater historical significance than the gold is the immense quantity of porcelain recovered by Hatcher: more than 150.000 pieces. The stylistic characteristics support a mid-18th century dating. The nature and composition of the goods, when we compare them with the shipping invoice of the Geldermalsen and other archival documents, are proof beyond doubt that what we see here before us is indeed the porcelain from the Geldermalsen.

We have a short but complete shipping invoice, thanks to the custom of that time to make several copies of nearly every written document. The VOC after all, had a great many pennisten or clerks in its service.

This list is a copy of the letter which was on its way to the Zeeland Chamber with the Geldermalsen. The Honourable Gentlemen receive, thus the letter, the usual survey of the cargo.

The Geldermalsen has 203 chests with porcelain on board with the following assortment (the original Dutch names are added between brackets): 171 dinner services (tafelserviesen), 63.623 tea cups and saucers (theegoed), 19.535 coffee cups and saucers (kofflegoed), 9.735 chocolate cups and saucers (chocoladegoed), 578 tea pots (trekpotten), 548 milk jugs (melkkommen), 14.315 flat dinner plates (tafelborden), 1.452 soup plates (soepborden), 299 cuspidors (quispedoren), 606 vomit pots (spuijgpoijes), 75 fish bowls (viskommen), 447 single dishes (enkele schalen), 1.000 nests round dishes (nest ronde schalen), 195 butter dishes (botervlooijes), 2.563 bowls with saucers (kommeijes en pieringen), 821 mugs or English beer tankards (mugs of Engelse bierkannen), 25.921 slop bowls (spoelkommen).

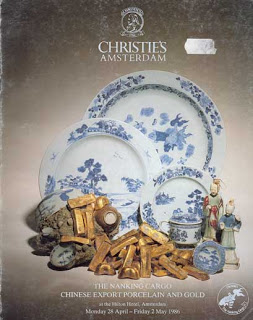

Christies Auction House appointed Mark Wrey to handle publicity. 'Nanking Cargo' was decided as the title for the sale, the name coming from 18th century auctions which advertised the porcelain as 'Nanking Ware'. It was the inspiration of Christie's Chinese Department Director Colin Sheaf who would later write a book of his own, 'The Hatcher Porcelain Cargoes'. One of Wrey's first moves was the compiling of a video of Bremner's footage. Four hundred advance copies were made and sent to dealers and to Christie's salerooms in London, New York, Amsterdam and Paris. A major press conference was held in Amsterdam for international newspaper and television journalists, with Mike Hatcher on show together with a range of artefacts from the Geldermalsen.

By Friday, 1 May 1986, Christies had sold almost 160.000 pieces of porcelain and 126 gold ingots for a total of 37 million guilders. That translated into 10 million sterling, or $US 20 million.

An extraordinary sum and beyond the wildest expectations of Christie's and Max de Rham. A record for any similar sale in Holland, the 2nd highest from any Christie's auction to that time.

From the New York Times

More than 100,000 pieces of Chinese porcelain and gold bullion from a European merchant ship - wrecked two centuries ago in the South China Sea and salvaged by a British captain and his crew - were sold this week in Amsterdam for $15,255,102, one of the highest totals ever in an auction of porcelains. Among the major buyers who were identified was David S. Howard, a London dealer, who paid $261,475 for a dinner service.

Comments

-

- 1. treasures On 30/06/2012

One says there are still gold ingots to find on the wreck location... -

- 2. Lulu On 10/01/2011

I have read the book 'Naufrage en mer de Chine' which is a French book i had to read for school. It was written around the real shipwreck of the Geldermalsen. The son, Max of the author, Anne de Preux, went diving and found 125 ingots of gold in the sips kitchen !!! It was realy good I sugest it to every 1 who likes books about live on boat !!!!!:D

Add a comment